The video and text which follows were prepared for the symposium Vukašin Pavlović - the Herald of Political Alternatives, Faculty of Political Science, University of Belgrade, April 22 2024.

Pozdrav sima, dobro jutro (from Sydney) dober dan. Zdravo de si ti Vukašin.

I was asked by the organisers of this symposium to say a few words about you and your work. It’s my honour and very great personal pleasure to do so.

We first met in Dubrovnik, at the Inter-University Centre, perhaps in the mid-1980s, but I remember more clearly the first moment we talked at length, in London, in the pre-digital age, after you had written a letter to me to say that you would like to meet, to discuss the work of CSD – it’s celebrating its 35th anniversary later this year – and to consider the possibility of cooperation with scholars and students in Yugoslavia.

The year was perhaps 1991. I recall it was spring. But for you personally, and politically, this was hardly springtime. Long, dark shadows were fast falling over Yugoslavia. The Soviet empire was imploding. The unification of Germany had begun. So had the violent disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Following the so-named ‘yoghurt revolution’, Miloševič, the banker turned demagogue nationalist, was on the warpath. His forces had already politically captured Kosovo, Vojvodina and Montenegro.

At the time, Vukašin and I could not have known the darker future: Slovenia and Croatia would declare formal independence (on June 25, 1991). The Yugoslav Army (JNA) attacked Slovenia but withdrew after 10 days. After the Serb minority in Croatia declared its own independence, the JNA intervened. The war that followed proved gruesome. It devastated Croatia; tens of thousands died, hundreds of thousands of people were displaced. After Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia (in May 1992) and Serbs there declared their own areas an independent republic war engulfed Bosnia-Herzegovina in flames and cruelty. Hundreds of thousands died; millions were forced from their homes. There was the horror of Srebenica. Europe witnessed the most horrific fighting on its territory since the end of World War II. In 1998–1999, violence erupted again in Kosovo, with the province’s majority Albanian population calling for independence from Serbia. Social resistance, economic stagnation and NATO bombs forced the Milosevic regime to accept a NATO-led international peace keeping force in a province under U.N. administrative mandate. Milosevic finally lost his grip on power in 2001. He was arrested and turned over to the International Crimes Tribunal in The Hague. As if it was his final revenge on the world, the demagogue died in prison in 2006, before his trial had concluded.

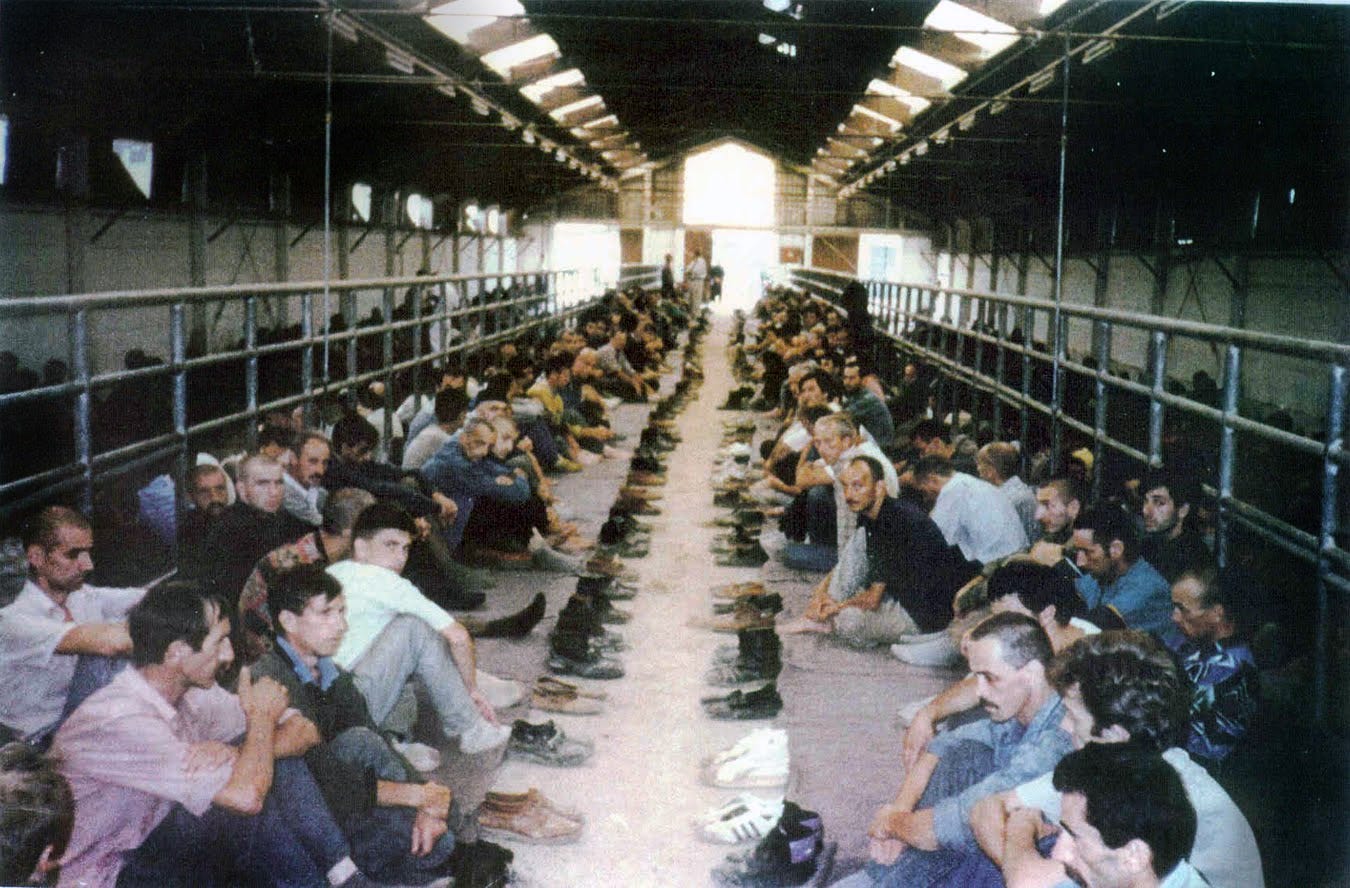

Bosnian Muslims, Croatians and other non-Serb civilian detainees in the Manjača concentration camp, where prisoners were beaten, raped and tortured, and more than 500 murdered and buried in a local mass grave, circa March 1992. Photograph provided courtesy of the ICTY.

Harsh and mesmerising times they were, and it’s therefore unsurprising that from the time of our London encounter Vukašin and I often spoke about the pities of violence and war. We puzzled over how and why well-established hybrid communities of different faiths, languages and national identities – the metonymic Yugoslavia of Ivo Andric’s Bridge on the Drina, a Yugoslavia that was the bridge between East and West, ‘partaking of both but being neither’ – could so easily be ripped apart. We talked about what all this meant for the whole idea of democracy, and why the once strange-sounding, now increasingly influential and popular neologism civilna druzba had great significance for the peoples of the former Yugoslavia.

These were the themes central to our first formal cooperation: the Yugoslav - British Summer School for Democracy, held in Budva, Montenegro in the summer of 1995. Working with Vukašin was a delight: I found him to be a thoughtful, politically savvy gentleman with a fine sense of humour and worldly wonder. For me the scholarly gathering was unforgettable, in more ways than one. There were minor dramas. In those times, getting to Budva wasn’t easy. On foot, Vukašin and I crossed the border from Croatia into the new Montenegro-Serbia Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the successor state to the old Yugoslavia, carrying hand luggage, passports in our back pockets on a back road unguarded by border police, hoping for the best, cackling with delight, with Vukašin carrying on his shoulder a replacement muffler which he’d purchased in Dubrovnik for his car in Beograd, where such commodities were in short supply.

Striking was the intensity and shared sense of urgency of the Budva Summer School discussions. The topics of violence, civil society, state power, and democracy felt deeply meaningful, and I believe that Vukašin’s subsequent writings on ‘suppressed civil society’ and the dangers of concentrated political power were shaped and enriched by the Budva gathering, and the many annual summer schools that followed.

Here there’s no room for nostalgia for times past, not only because all of these themes arguably still have enormous intellectual and public significance in Vučić’s Serbia and the wider region, but also because as summer school organiser, intellectual and friend Vukašin Pavlović was, and remains, a role model, an exemplar, of the philosophical and political virtues under examination in Budva. From the outset, I considered him a personal mentor. A fun-loving man who liked to joke, even kick around a football (though he’s not to be confused with his doppelgänger Vukašin Pavlović of ex-Voždovac Serbian SuperLiga fame!). A man of impeccable integrity, always reliable and trustworthy, someone who doesn’t tell lies or spread bullshit. An ironist who practised the art of seeing and living the world in at least two different ways. A man of courage who periodically took serious risks, for instance by resigning after several terms as Dean of the Political Science Faculty in defence of university autonomy. A person of humility who would blush and chuckle when addressed as Professor Dr. Vukašin Pavlović…

For all these reasons and more, I came to consider Vukašin a public intellectual and political sociologist well ahead of his time. He has constantly reminded his readers and listeners of the historical reasons why Serbian has been plagued by a ‘leader cult’, the ethos of machismo and militarism, and why many Serbs are attracted to despotic rather than democratic modes of rule. Well ahead of his generation, he rightly warned against eco-destruction and was among the first thinkers I know who foresaw that anthropocentric understandings of civil society and democracy would need to be replaced by ‘greener’ and more caring understandings of how we humans are dwellers on Earth, and that (whatever Elon Musk says) there’s no known cure for that and no known escaping to other parts of our galaxy. Vukašin has consistently been a thinker of precaution, neither a pessimist nor an optimist, a critic and scholar who stood firmly against abuses of power and their resulting pathologies. He saw clearly that in practice the normative ideal of civil society implied the need for defending a plurality of ways of life, overcoming hubris, downsizing the pompous by saying and doing things that in a small way help to shake the world and stop it falling asleep.

Intellectually speaking, Vukašin has indeed been a herald of political alternatives and a visionary of the utopian energies of civil society (Professor Dr. Dragica Vujadinović). He anticipated and helped make possible and make sense of the later emergence of a robust civil society, for instance during the ‘pots and pans’ protests against Milošević during the winter of 1996/97 – a style of democratic resistance to despotic rule that since then has periodically resurfaced, most recently in protests against eco-destruction and in the Serbia Against Violence coalition declarations of Beograd as a free city committed to free and fair elections without kleptocracy, bought votes and stuffed ballot boxes.

Professor Vukašin Pavloviċ, Belgrade, October 2021

But in closing there’s one other less obvious and vitally attractive thing I’d like to say about you, Vukašin. I spotted at an early point that you were against blind despair and dogmatic pessimism and that instead you stood on the side of hope (nadatise). In extremely trying circumstances, you saw that the vision of a civil society protected by law, democratically elected governments and public watchdog institutions both requires hope and, just as importantly, is the condition of possibility of hope. You understood that civil societies nurture and nourish hope, and that they do so in several ways.

When they work well, the inner pluralism, dynamism and self-reflexivity of any given civil society stirs up a sense of possibility among citizens and their representatives that things can be other than they currently are. Robust civil societies, their refusal of violence and public commitment to identity sharing and the general restraint of arbitrary exercises of power, from the bedroom through the boardroom to the election battlefield, enable the peaceful living together and rubbing along and adjudication of differences among often competing and conflicting hopes.

More than this, and of great relevance in our darkening times, vibrant civil societies have built-in early warning detectors against metaphysical, big talk Grand Ideologies - the Nation, the People, the Market or God - that promise heaven on earth but in reality serve to destroy complexities and threaten the ideals of openness, pluralism and power sharing.

Vukašin: you have taught us that hope shouldn’t be confused with naïve optimism or its twin opposite, dogmatic pessimism. Hope lives in the land between absolute certainty and absolute impossibility. Hope is not belief in miracles. It is not rainbows of the mind. It is not acting cheerfully in grim circumstances. Hope is both a noun and a verb. It has a pragmatic quality. It is prudent, realistic, and active. Hope comes wrapped in possibility, not probability.

Hope is indeed a gamble. It risks disappointment, but to hope – as you explained to me in London the first time we talked at length - is to feel that things as they are can be changed, and to experience joy at the very thought that what IS does not equal what COULD BE. Hope flies with swallow’s wings. Hope is grace, it is medicine for the miserable (Shakespeare). Hope lifts people’s spirits by encouraging them to look beyond their present horizons, to expect and to demand improvements.

We are all in your debt, Vukašin, because in your research and writings on power and civil society you convincingly taught us that hope is often the only thing that keeps our hearts from breaking – and that in a grim age when millions of people are feeling the pinch of pessimism, resentment, cynicism and despair, scholars and citizens must prepare themselves for the worst so that they can take advantage of what they have, and what comes their way, in order to build a better future for themselves, and for the ecosystems in which they dwell.

Hvala svima na željama….hvala vam puno! Thank you very much.

Further details of the symposium are available at: https://url.au.m.mimecastprotect.com/s/MfmdC0YKPviJmA8m8HwfU4d?domain=fpn.bg.ac.rs

Share this post