Democracy and Its Enemies

An introduction to a new series

Millions of citizens around the world are today asking questions of grave importance: What’s happening to democracy, a way of governing and living that until recently was said to have enjoyed a global victory? Why is it everywhere reckoned to be in retreat, or facing extinction? They’re surely right to wonder.

Three decades ago, democracy seemed blessed. People power mattered. Public resistance to arbitrary rule changed the world. Military dictatorships collapsed. Apartheid was toppled. There were velvet revolutions, followed by tulip, rose, and orange revolutions. Political rats like Nicolae Ceauşescu, Augusto Pinochet, Slobodan Milošević and Pol Pot were arrested or put on trial, suffered death in custody or were shot on the spot.

Now things are different. In Belarus, Bolivia, Myanmar, Hong Kong, and other places, citizens are the victims of arrest, imprisonment, beating, and execution. Elsewhere, democrats generally seem to be on the back foot, gripped by feelings that our times are weirdly unhinged, and troubled by worries that big-league democracies such as India, the United States, Britain, South Africa, and Brazil are sliding toward a precipice, dragged down by worsening social inequality, citizen disaffection, and the rot of unresponsive governing institutions.

Fears are growing that democracy is being sabotaged by angry popular support for demagogues, or by surveillance capitalism, pestilence, the rise of China, and Putin-style despots who speak the language of democracy but don’t care a fig for its substance. And now there is the horror, carnage and day-and-night destruction raining down on the people of Ukraine. At the same time, complacency, and scepticism are on the rise: There are those who say talk of the sickness and coming death of democracy is mostly melodrama—overheated description of what is only a passing period of political reckoning and structural readjustment.

This Democracy and Its Enemies series is inspired by these tough questions and doubts to offer a compact reply: While practically all democracies are facing their deepest crisis since the 1930s, we are by no means in a replay of that dark period. Yes, powerful economic and geopolitical forces are once again gaining the upper hand against the spirit and substance of democracy. The great pestilence that began sweeping the world in 2020 has made things far worse, as an influenza pandemic did a century earlier. The ancient adage that ordinary folk count for nothing and democracy is a cloak for the rich is surely still partly true. So is the spread of whip-hand policing and surveillance of disillusioned citizens. With the gradual decline of the United States, the re-emergence of a self-confident Chinese empire, and the unending disorders occasioned by the breakup of the Soviet Union and Arab-region despotism, our times are hardly less tumultuous or momentous. And yet—the qualification is fundamental—our times are so troubling and puzzling exactly because they are different.

A Hopeful History

Understanding how our times are unique requires us to take the past seriously. But why? How is the remembrance of things past not just helpful but vital in considering the fate of democracy in these troubled years of the twenty-first century? Most obviously, history matters because when we are ignorant of the past we invariably misunderstand the present. We lose the measure of things. Unforgetting makes us wiser. It helps us make better sense of the new trials and troubles faced by most present-day democracies.

There’s something else. This Democracy and Its Enemies series sets out to stir up a sense of wonder about democracy. It’s no antiquarian encounter with things past, a history for the sake of history. It’s more like an odyssey filled with unexpected twists and turns, a story of those defining moments when democracy was born, or finally matured, or came to a sticky end. The series tracks the long continuities, gradual changes, crises, and sudden upheavals that have defined its history. It will pay attention to past shocks and setbacks when democracy suffered a crushing blow, or committed democide. The series will put its fingers on puzzles—why democracy has typically been portrayed as a woman, for example—and spring a few surprises. It will also aim to unsettle orthodoxies.

History can make mischief. Democracy and Its Enemies bids farewell to the cliché that democracy was born in Athens and the bigoted belief that the early Islamic world contributed nothing to the spirit and institutions of democracy. It makes the case for a world history of democracy and therefore rejects political scientist Samuel P. Huntington’s influential but one-eyed claim that the most important development of our generation is the “third wave” of American-style liberal democracy triggered by events in southern Europe in the early 1970s. It shows why democracy is much more than periodic “free and fair” elections, as Huntington thought, and why the birth of the new form of what I’ve called monitory democracy in the years after 1945 has been far more consequential, and remains so today.

‘Is there a democratic way of speaking about democracy?’ asked Nicole Loraux (1943–2003), a scholar of classical Athens revered for her pioneering accounts of the myths, politics and gendered discourses and institutions of early democracy.

There’s one thing this series is not: a gloomy tale of catastrophes. In paying attention to democracy’s braided fortunes, it does not strengthen the spirits of doubters and despots by warning in know-it-all fashion that, when it comes to democracy, everything usually ends badly. The contributions agree with the distinguished French classics scholar Nicole Loraux: The history of democracy has principally been recorded by its enemies, such as the ancient Greek historian and military general Thucydides (c. 460–400 BCE) and the Florentine diplomat and political writer Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527). By contrast, the pages to follow take the side of democracy, but they try hard to ditch illusions and biases and guard against the danger that history can come to resemble a big bag of tricks played by the living on the dead. Democracy has no need of memory police. The series doesn’t suppose that it is the last word on democracy because it knows everything about its past; or that it knows in advance that, despite everything, all will turn out well, or badly. It’s neither foolishly optimistic nor dogmatically pessimistic about the future. It is, rather, the bearer of hope.

The spiky defence of democracy running through the pages to come draws strength from the remembrance of the fallen. It is inspired by encounters with a host of oft-forgotten characters who ate, drank, laughed, sighed, cried, and died for democracy; people from distant pasts whose inspiring words and deeds remind us that democracy, carefully understood, remains the most potent weapon yet invented by humans for preventing the malicious abuse of power. Democracy and Its Enemies investigates the obscure origins and contemporary relevance of old institutions and ideals, such as government by public assembly; votes for women, workers, and freed slaves; the secret ballot; trial by jury; and parliamentary representation. Those who are curious about political parties, periodic elections, referenda, independent judiciaries, truth commissions, bio-regional assemblies, civil society, and civil liberties such as press freedom will get their fill. So, too, will those interested in probing the changing, often hotly disputed meanings of democracy, or the cacophony of conflicting reasons given for why it is a good thing, or a bad thing, or why one impressive feature of democracy is that it gives people a chance to do stupid things and then change their minds, and other jokes usable at any election-night party.

Among the funniest jokes about democracy, said Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Reich minister of propaganda, is that it gives its enemies the means to destroy it—and, we could add, grind its memories into the dust of time. Let’s take this fascist bad joke to heart. Several times in the past, democracies have stumbled, and fallen, and sometimes never recovered. This Democracy and Its Enemies series is a precautionary tale, but it has a sharp edge. It shows that history isn’t storytelling that sides with the enemies of democracy. It is not an epitaph, a sad tale of ruin recorded in prose and footnotes. To paraphrase the eighteenth-century sage Voltaire (1694–1778), it is not the sound of silk slippers upstairs and wooden clogs below. Far from being a sequence of horrors, it shows that history can come to the defense of underdogs. History is not obituary; it can inspire by reminding us that the precious invention called democracy is usually built with great difficulty, but so easily destroyed by its enemies, or by thoughtlessness, or by lazy inaction.

Against Titanism

Although democracy has no built-in guarantees of survival, it has regularly been the midwife of political and social change. Here we come to a puzzling point with far-reaching consequences. Democrats not only altered the course of history—for instance, by shaming and dumping monarchs, tyrants, corrupt states, and whole empires run by cruel or foolish emperors. It can be said—here’s a paradox—that democracy helped make history possible. When democracy is understood simply as people governing themselves, its birth implied something that continues to have a radical bite: It supposed that humans could invent institutions that allow them to decide, as equals, how they will live together on our planet. This may seem rather obvious; but think about its significance for a moment. The idea that breathing, blinking mortals could organize themselves into forums where they deliberate on matters of money, family, law, and war as peers and decide on a course of action—democracy in this sense was a spine-tingling invention because it was in effect the first-ever malleable form of government.

Compared with political regimes such as tyranny and monarchy, whose legitimacy and durability depend upon fixed and frozen rules, democracy is exceptional in requiring people to see that everything is built on the shifting sands of time and place, and so, in order not to give themselves over to monarchs, emperors, and despots, they need to live openly and flexibly. Democracy is the friend of contingency. With the help of measures such as freedom of public assembly, anticorruption agencies, and periodic elections, it promotes indeterminacy. It heightens people’s awareness that how things are now is not necessarily how they will be in future. Democracy spreads doubts about talk of the “essence” of things, inflexible habits, and supposedly immutable arrangements. It encourages people to see that their worlds can be changed. Sometimes it sparks revolution.

Democracy has a sauvage (wild) quality, as the French thinker Claude Lefort (1924–2010) liked to say. Its punk quality tears up certainties, transgresses boundaries, and isn’t easily tamed. Democracy invites people to see through talk of gods, divine rulers, and even human nature; to abandon all claims to an innate privilege based on the “natural” superiority of brain or blood, skin colour, caste, class, religious faith, age, or sexual preference. Democracy denatures power.

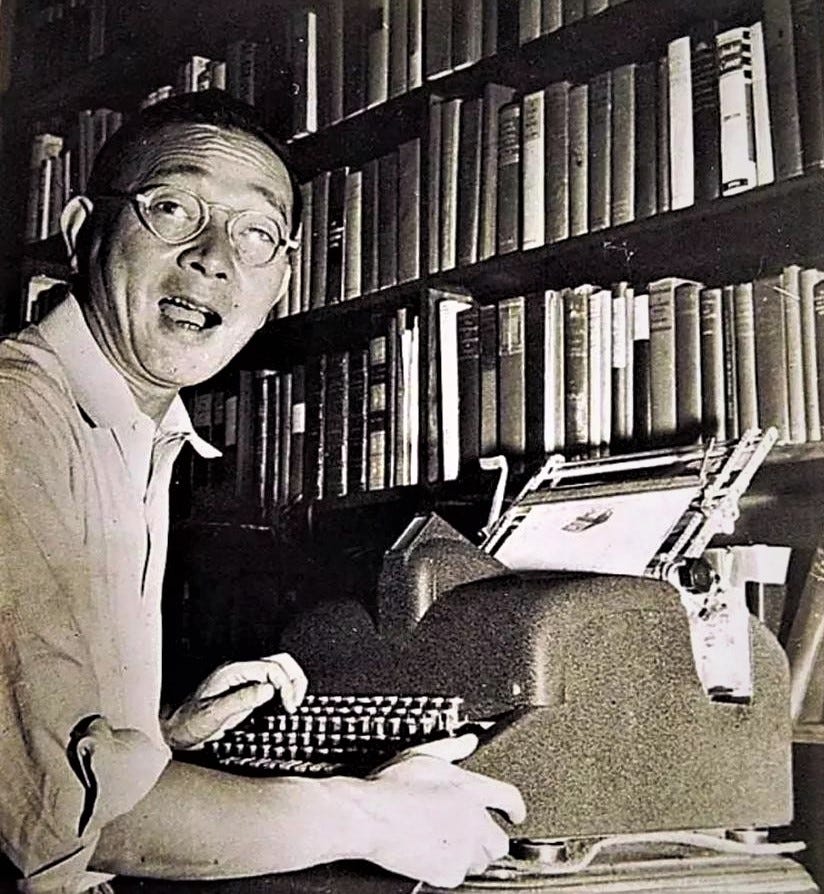

Encouraging people to see that their lives are open to alteration, democracy heightens awareness of what is arguably the paramount political problem: how to prevent rule by the few, the rich, or the powerful, who act as if they are mighty immortals born to rule? Democracy solves this old problem of titanism—rule by pretended giants—by standing up for a political order that ensures who gets how much, when, and how is a permanently open question. From its inception, democracy recognized that although humans were not angels, they were at least good enough to prevent others from behaving as if they were. And the flip side: Since people are not saintly, nobody can be trusted to rule over others without checks on their power. Democracy supposes, the Chinese writer Lin Yutang (1895–1976) once said, that humans are more like potential crooks than honest gentlefolk, and that since they cannot be expected always to be good, ways must be found of making it impossible for them to be bad. The democratic ideal is government of the humble, by the humble, for the humble. It means rule by people, whose sovereign power to decide things is not to be given over to imaginary gods, the stentorian voices of tradition, autocrats, or experts, or simply forfeited to unthinking laziness, allowing others to decide matters of public importance.

Chinese satirist and writer Lin Yutang at work on his invention, a Chinese-character typewriter. His writings mocked the propaganda and censorship of the 1930s Nationalist government. The first of his many English-language books, My Country and My People (1935), became a bestseller.

Surprises and Secrets

Since democracy encourages people to see that nothing of the human world—not even so-called human nature—is timeless, its history is punctuated with extraordinary moments when, against formidable odds, and despite all expectations and predictions, brave individuals, groups, and organizations defied the status quo, toppled their masters, and turned the world upside down. Democracy often takes reality by surprise. It stands on the side of earthly miracles. The dramatic arrest and public execution of kings and tyrants, unplanned mutiny of disgruntled citizens, unexpected resistance to military rule, and cliff-hanger parliamentary votes are among the dramas that catch the living by surprise and leave those who come after fascinated by how and why such breakthroughs occurred. Making sense of these dramas of democratic triumph is challenging. It requires letting go of ground-solid certainties. It forces us to open our eyes in full wonder to events made more marvelous by the fact that democracy carefully guards some of her oldest and most precious secrets from the prying minds of later generations.

Consider an example: the fact that democracy in both ancient and modern times has often been portrayed as a woman. The 2019 protests that led to the overthrow of the Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir included a white-robed student protester, Alaa Salah, who was revered for her spirited crowd-dancing and calls for demonstrators to stand up for dignity and decency. The 2019 summer uprising of Hong Kong citizens against mainland Chinese rule saw her appear, thanks to crowdsourced funding, as a four-meter-high statue, equipped with helmet, goggles, and gas mask, clutching a pole and an umbrella. In the ill-fated 1989 occupation of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, democracy, designed by students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, appeared as a goddess bearing a lighted lamp of liberty.

Going back in time, the Italian artist Cesare Ripa of Perugia (c 1555–1622) depicted democracy as a peasant woman holding a pomegranate—a symbol of the unity of the people—and a handful of writhing snakes. And, thanks to the work of twentieth-century archaeologists, we have evidence of a goddess named Dēmokratia worshipped by the citizens of Athens (who were all male) in exercising their right to resist tyranny and to gather in their own assembly, under their own laws.

Alaa Salah, symbol of a people’s uprising, atop a car and dressed in a white thoub, leading chants for the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in Khartoum in April 2019.

Our detailed knowledge of her in that context is limited; in matters of democracy, time’s arrow doesn’t fly in a predictably clear line. But we do know that the noun used by Athenians for nearly two centuries to describe their way of life—dēmokratia—was feminine. We also know that democratic Athens had the firm backing of a deity—a goddess who refused marriage and maternity, and was blessed with the power of molding men’s hopes and fears. Athenians did more than imagine their polity in feminine terms: Democracy itself was likened to a woman with divine qualities. Dēmokratia was honored and feared, a transcendent figure blessed with the power to give or take life from her earthly supplicants—the men of Athens. That was why a fleet of Athenian warships was named after her, and why buildings and public places were adorned with her image.

In the 1643 French edition of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593), a widely read book of emblems and virtues, democracy is presented as a coarsely dressed peasant woman. Until well into modern times, democracy was dismissed as a dangerously outdated (Greek) ideal that licensed the uncouth and the unwashed.

In the northwest corner of the public square known as the agora, nestled beneath a hill topped by a large temple that survives today, stood an impressive colonnaded building, a civic temple known as the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios. The interior was lavishly decorated, with a glorious painting of Democracy and the People by a Corinth artist named Euphranor. Exactly how he portrayed them remains a riddle. The paintings have not survived, yet they serve as a reminder of the intimate link between democracy and the sacred, and of the vital role of the Athenian belief that a goddess protected its polity.

The point is driven home by the most famous surviving image of Dēmokratia from ancient Athens. Carved in stone above a law from 336 BCE, it shows the goddess adorning, shielding, and sheltering an elderly bearded man who represents the dēmos, the people. There’s evidence that the goddess Dēmokratia attracted a cult following of worshippers, and that her sanctuary was also located in the agora. If that’s true, there would have been a stone altar on which citizens, assisted by a priestess, recited prayers of gratitude and offered sacrifices, such as cakes, wine, and honey, a slaughtered goat or a spring lamb. There might have been theoxenia, invitations to the imagined goddess to dine as guest of honour while reclining on a splendid couch.

The priestess, duty-bound to ensure the goddess was shown due respect, would have been appointed from a leading Athenian family, or nominated or chosen by lot, perhaps after an oracle was consulted. A female operator in a man’s world, the priestess had mysterious authority that could not be profaned, except at the risk of punishment, which ranged from cold-shouldering and bad-mouthing to exile and death. In return, the priestess helped to protect democratic Athens from misfortune, and from its enemies. The arrangement had a corollary. The misbehaviour of the public assembly—for example, foolish decisions by its prominent citizens—risked payback, such as the failure of the olive crops, the disappearance of fish from the sea, or, as we are going to see in this series, democide: the self-destruction of democracy.

Our great misfortune – our great opportunity, this Democracy and Its Enemies series sets out to show - is that we mortals on planet Earth are nowadays on our own. We’ve been abandoned. The deities have departed. No God can save us from ignorance, pride, prejudice, complacency, bossing and bullying. We have no goddess to protect our democracies from democide, and no way of stopping the dedicated enemies of democracy from getting the upper hand except through creative thinking and active political commitments to keeping alive the spirit and substance of power-sharing democracy.